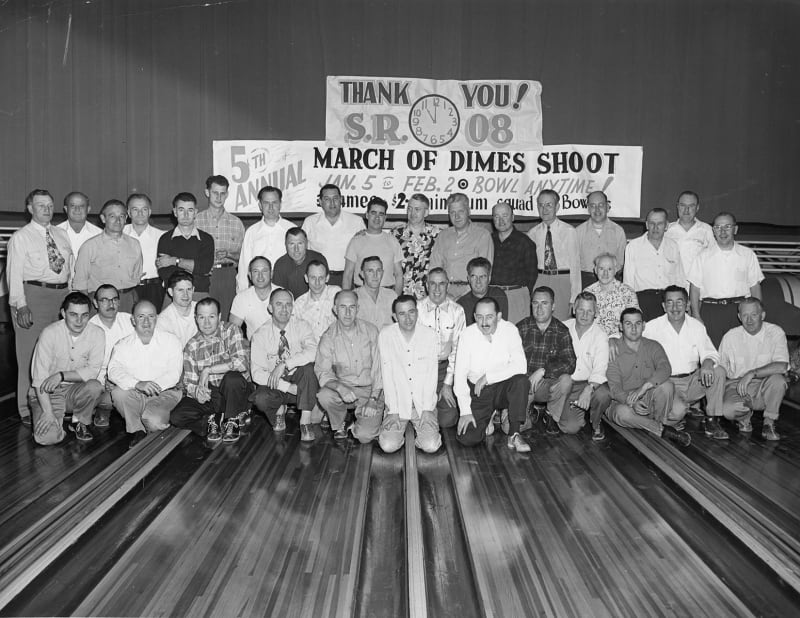

Elks Lodge Bowling Team, c. 1950s. Marin History Museum Collection.

In his 2000 book Bowling Alone, Harvard professor Robert Putnam lamented America’s decline in social and community life. He used the sport to represent the loss of membership and involvement by Americans in organized civic organizations, such as PTA’s; political parties; church, neighborhood and volunteer groups; and bowling leagues. Putnam worried about the consequences, fearing the weakening of the social fabric required for a healthy society and democracy. He was alarmed by the shift to more individual pursuits and its correlation with public alienation, lower educational performance, poor public health, greater teen delinquency, and higher crime rates.

Bowling has been a bellwether for this shift. Although the number of individual Americans who bowled had increased in the two decades prior to Putnam’s book, bowling on teams in bowling leagues had dramatically declined. This trend has continued: while 9 million Americans bowled on league teams in 1981, only 2 million do so today. Not only are few Americans participating in organized bowling but their ability to even do so has also declined. Between 1998 and 2014, the number of U.S. bowling alleys declined from 5500 to 4000. Now fewer than 3800 remain and they keep disappearing. Altogether, two thirds of all U.S. alleys have closed since their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s when they were a defining part of American culture.

Marin has followed this trend. Bowling alleys in the county date back more than a century but they’re all gone now. As early as the 1880s, Mill Valley’s Blithedale Hotel offered overnight lodging for tourists as well as summer homes for San Francisco businessmen. Its 342 acres featured the main hotel building as well as cottages and small houses. Recreationally, it offered tennis, billiards, saddle horses, and a bowling alley for its guests until it closed in 1910.

In the 1890s, San Rafael’s Hotel Rafael offered similar attractions. Located in the Dominican neighborhood near the current Belle Avenue and Rafael Drive intersection, its grand entrance pillars still survive the resort’s destruction by fire in 1928. Facing Mount Tamalpais, it accommodated 300 guests and boasted fine cuisine, saddle and carriage horses, tennis courts, and a separate clubhouse featuring smoking, card, reading, and billiard rooms. And its bowling alleys were advertised as “the best and most capacious of any hotel on the Coast.”

In 1908, Sam Black opened his ten-pin bowling alley on Miller Avenue in Mill Valley, across from the railroad depot. He reserved Tuesday and Friday afternoons for ladies and their escorts. Black sold the alley when neighbors complained about noise it generated late into the night. The Hub Theater began operating in Mill Valley in 1915. When it stopped showing films in 1929, it then served as a bowling alley and skating rink until it was bought by the Odd Fellows Temple in 1952. It became a IOOF Lodge and then a vaudeville and silent film venue until it transformed into the current Throckmorton Theater in 2003.

An Air Force Station was established on Mount Tamalpais in 1942 during World War II. It began as a radar site, scanning for Japanese ships, airplanes and submarines. It expanded during the 1950s Cold War era as a defense radar station. Its land and 62 buildings included a pool, bathhouse, theater, tennis court, and a bowling alley among its recreational facilities. The alley closed when the station was re-purposed in the 1980s. Another small Marin alley opened in the 1950s. The Third Street Alley in San Rafael operated from the property where a CVS pharmacy now stands. Games cost only 10 cents and the alley was still using human pin setters before it closed in the 1960s.

A much bigger and more popular alley opened in 1960. Nave Lanes, located at the intersection of Ignacio Boulevard and Nave Drive in Novato was designed by Gordon Phillips, a Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice. It featured a distinctive Wrightian style, similar to the Marin County Civic Center. Nave’s featured active bowling leagues and its Nero’s restaurant drew crowds not only for its snacks but also its cocktails and dinners, including big Italian Columbus Day feasts. Like a lot of bowling lanes of that era, it was a family operation and the alley was run by two generations of the Nave clan until it closed in 1999 to make way for retail outlets.

While some have dated the Greenbrae Lanes back to 1960, the bowling center emerged mostly in the 1970s from the second phase construction at the Greenbrae Shopping Center. The alley sat next to Zim’s at Drake’s Landing, down the street from the current Bon Air Center along Sir Francis Drake Boulevard. It was very popular through the 1980s for its league nights, its great French fries, and as a major gathering spot for Marin life. In the 1960s, a bowling alley also opened at Hamilton Field in Novato. Initially a U.S. Air Force base, the site was decommissioned and transferred to the Air Force Reserve in the 1970s and then designated as a U.S. Army Airfield until 1988. Housed in Facility 115, the Hamilton Gymnasium and Bowling Alley still stands on San Pablo Avenue southwest of the Escolta Avenue intersection. Open to the public, the alley’s six lanes were expanded to ten in 1975. The alley continued to operate after the base was turned over to civilian use in the late 1980s.

Along with many other Hamilton buildings, the gym was constructed with a Spanish eclectic style in 1934 and thus has been recognized by the U.S. Historic American Buildings Survey has having historic value. The survey’s 1995 report described the bowling alley as having “an oak floor, wooden truss ceiling, and gypsum wallboard . . . The snack bar, lounge area, and pro shop have carpeted floors, acoustical ceilings, and composition wallboard . . . [and] the alley has an automatic pin spotting machine.” Although the lanes closed in 2010, the building remains, awaiting restoration.

The last holdout in Marin was Country Club Bowl on Vivian Street in San Rafael. It opened in 1959 as a state-of-the art alley and survived for more than 60 years as a beloved destination for teens, families and serious bowlers. Its giant neon bowling-pin sign, visible from Highway 101, was a major Marin landmark. Boasting 40 lanes, the alley hosted dozens of teams and leagues over the years. The first alley in California to install a fully automatic scoring system, it was also known for its billiard room and “luxurious” Candlestick Lounge, featuring a retro bar displaying vintage photos of the venue’s history.

In 2016, Country Club began making upgrades and added the Villa York Pizza & Grill, which became a popular restaurant known for its pesto dishes and family dining. In 2019, new ownership planned to further modernize the lanes but the COVID-19 lockdowns intervened and structural damage in the building’s roof doomed the update. Closed in 2021, the alley was scheduled for demolition when it was sold to a developer for new housing, sparking a debate about lost youth facilities and local needs.

The demise of all these Marin venues has not only meant the loss of central and historic community hubs. It’s also been the loss of the unique bowling alley experience and the memories it provided. Even with your eyes closed, you’d know immediately when you entered an alley. Before you reached the lanes, the smells would jump out at you: the musty shoes, the pine or maple wood, the often-grungy balls, the greasy but alluring food, and maybe a little perspiration. But no matter. And then the familiar sounds of balls rolling heavily, the pop of the pins being hit or the wobble of a gutter ball, and the clanking of the automatic pin setters or the frantic scurrying of the “pin boys” setting up for the next throw. The endless clamor and the excited screams or groans after every shot.

And then the challenging search for just the right ball, rarely your first or second pick. Learning to keep score until automatic scoring took over. Slipping away for a burger or a dog, with fries and a soda, and maybe a drink at the bar for the adults. Hanging out with friends and the special events: the raucous birthday parties, the holiday specials, or the charity benefits. And for many bowlers, it meant the camaraderie and friendly competition of the teams and leagues for men, women, seniors, and kids.

All that is gone from Marin. Onetime alternatives, both the Albany Bowl and Richmond’s Uptown Bowl have now also closed. Those living in southern Marin could try the small Presidio Bowl in San Francisco. People living up north have better prospects since somehow Sonoma County bowling has hung on longer. Petaluma’s AMF Lanes or Rohnert Park’s Double Decker Lanes may not be too far to drive.

But the bowling options for Marin’s 250,000 residents keep disappearing. High operating costs for utilities, property taxes, and maintenance have been a deterrent. Typically occupying large tracts of real estate, alley owners find it more profitable to sell the land to developers for housing or retail spaces. The pandemic kept alleys closed for long stretches. And the younger generation might be less attracted to the commitment of teams and leagues, which help keep alleys in business. The new or surviving lanes tend to be expensive high-end boutique chains or alleys buried in a few high tech, multi-activity, family entertainment centers. Run by corporations or private equity firms, these are a far cry from the old, family run, neighborhood alleys.

eared we were losing. In 2000, he predicted the revival of civic organizations and the “social capital” needed for a democracy. But it never happened. Instead, the country has experienced a decline in civility and the disappearance of community and national bonds. Of course, it goes beyond the loss of communal bowling and extends to most American institutions. A profound sense of political alienation has gripped the nation. In the 2017 book, One Nation After Trump, the authors showed that the decline of the civic and social groups (that Putnam championed) had helped elect Donald Trump as “many rallied to him out of a yearning for forms of community and solidarity that they sense have been lost.”

If recent Facebook and Reddit posts are any indication, Americans—including Marin residents--sorely miss the lost community of bowling and wish alleys would make a comeback. Maybe their revival wouldn’t hurt the country, either.

Robert Elias is emeritus professor of Politics at the University of San Francisco, a Marin History Museum volunteer, and editor of the Mill Valley Historical Society Review.

Bowling has been a bellwether for this shift. Although the number of individual Americans who bowled had increased in the two decades prior to Putnam’s book, bowling on teams in bowling leagues had dramatically declined. This trend has continued: while 9 million Americans bowled on league teams in 1981, only 2 million do so today. Not only are few Americans participating in organized bowling but their ability to even do so has also declined. Between 1998 and 2014, the number of U.S. bowling alleys declined from 5500 to 4000. Now fewer than 3800 remain and they keep disappearing. Altogether, two thirds of all U.S. alleys have closed since their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s when they were a defining part of American culture.

Marin has followed this trend. Bowling alleys in the county date back more than a century but they’re all gone now. As early as the 1880s, Mill Valley’s Blithedale Hotel offered overnight lodging for tourists as well as summer homes for San Francisco businessmen. Its 342 acres featured the main hotel building as well as cottages and small houses. Recreationally, it offered tennis, billiards, saddle horses, and a bowling alley for its guests until it closed in 1910.

In the 1890s, San Rafael’s Hotel Rafael offered similar attractions. Located in the Dominican neighborhood near the current Belle Avenue and Rafael Drive intersection, its grand entrance pillars still survive the resort’s destruction by fire in 1928. Facing Mount Tamalpais, it accommodated 300 guests and boasted fine cuisine, saddle and carriage horses, tennis courts, and a separate clubhouse featuring smoking, card, reading, and billiard rooms. And its bowling alleys were advertised as “the best and most capacious of any hotel on the Coast.”

In 1908, Sam Black opened his ten-pin bowling alley on Miller Avenue in Mill Valley, across from the railroad depot. He reserved Tuesday and Friday afternoons for ladies and their escorts. Black sold the alley when neighbors complained about noise it generated late into the night. The Hub Theater began operating in Mill Valley in 1915. When it stopped showing films in 1929, it then served as a bowling alley and skating rink until it was bought by the Odd Fellows Temple in 1952. It became a IOOF Lodge and then a vaudeville and silent film venue until it transformed into the current Throckmorton Theater in 2003.

An Air Force Station was established on Mount Tamalpais in 1942 during World War II. It began as a radar site, scanning for Japanese ships, airplanes and submarines. It expanded during the 1950s Cold War era as a defense radar station. Its land and 62 buildings included a pool, bathhouse, theater, tennis court, and a bowling alley among its recreational facilities. The alley closed when the station was re-purposed in the 1980s. Another small Marin alley opened in the 1950s. The Third Street Alley in San Rafael operated from the property where a CVS pharmacy now stands. Games cost only 10 cents and the alley was still using human pin setters before it closed in the 1960s.

A much bigger and more popular alley opened in 1960. Nave Lanes, located at the intersection of Ignacio Boulevard and Nave Drive in Novato was designed by Gordon Phillips, a Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice. It featured a distinctive Wrightian style, similar to the Marin County Civic Center. Nave’s featured active bowling leagues and its Nero’s restaurant drew crowds not only for its snacks but also its cocktails and dinners, including big Italian Columbus Day feasts. Like a lot of bowling lanes of that era, it was a family operation and the alley was run by two generations of the Nave clan until it closed in 1999 to make way for retail outlets.

While some have dated the Greenbrae Lanes back to 1960, the bowling center emerged mostly in the 1970s from the second phase construction at the Greenbrae Shopping Center. The alley sat next to Zim’s at Drake’s Landing, down the street from the current Bon Air Center along Sir Francis Drake Boulevard. It was very popular through the 1980s for its league nights, its great French fries, and as a major gathering spot for Marin life. In the 1960s, a bowling alley also opened at Hamilton Field in Novato. Initially a U.S. Air Force base, the site was decommissioned and transferred to the Air Force Reserve in the 1970s and then designated as a U.S. Army Airfield until 1988. Housed in Facility 115, the Hamilton Gymnasium and Bowling Alley still stands on San Pablo Avenue southwest of the Escolta Avenue intersection. Open to the public, the alley’s six lanes were expanded to ten in 1975. The alley continued to operate after the base was turned over to civilian use in the late 1980s.

Along with many other Hamilton buildings, the gym was constructed with a Spanish eclectic style in 1934 and thus has been recognized by the U.S. Historic American Buildings Survey has having historic value. The survey’s 1995 report described the bowling alley as having “an oak floor, wooden truss ceiling, and gypsum wallboard . . . The snack bar, lounge area, and pro shop have carpeted floors, acoustical ceilings, and composition wallboard . . . [and] the alley has an automatic pin spotting machine.” Although the lanes closed in 2010, the building remains, awaiting restoration.

The last holdout in Marin was Country Club Bowl on Vivian Street in San Rafael. It opened in 1959 as a state-of-the art alley and survived for more than 60 years as a beloved destination for teens, families and serious bowlers. Its giant neon bowling-pin sign, visible from Highway 101, was a major Marin landmark. Boasting 40 lanes, the alley hosted dozens of teams and leagues over the years. The first alley in California to install a fully automatic scoring system, it was also known for its billiard room and “luxurious” Candlestick Lounge, featuring a retro bar displaying vintage photos of the venue’s history.

In 2016, Country Club began making upgrades and added the Villa York Pizza & Grill, which became a popular restaurant known for its pesto dishes and family dining. In 2019, new ownership planned to further modernize the lanes but the COVID-19 lockdowns intervened and structural damage in the building’s roof doomed the update. Closed in 2021, the alley was scheduled for demolition when it was sold to a developer for new housing, sparking a debate about lost youth facilities and local needs.

The demise of all these Marin venues has not only meant the loss of central and historic community hubs. It’s also been the loss of the unique bowling alley experience and the memories it provided. Even with your eyes closed, you’d know immediately when you entered an alley. Before you reached the lanes, the smells would jump out at you: the musty shoes, the pine or maple wood, the often-grungy balls, the greasy but alluring food, and maybe a little perspiration. But no matter. And then the familiar sounds of balls rolling heavily, the pop of the pins being hit or the wobble of a gutter ball, and the clanking of the automatic pin setters or the frantic scurrying of the “pin boys” setting up for the next throw. The endless clamor and the excited screams or groans after every shot.

And then the challenging search for just the right ball, rarely your first or second pick. Learning to keep score until automatic scoring took over. Slipping away for a burger or a dog, with fries and a soda, and maybe a drink at the bar for the adults. Hanging out with friends and the special events: the raucous birthday parties, the holiday specials, or the charity benefits. And for many bowlers, it meant the camaraderie and friendly competition of the teams and leagues for men, women, seniors, and kids.

All that is gone from Marin. Onetime alternatives, both the Albany Bowl and Richmond’s Uptown Bowl have now also closed. Those living in southern Marin could try the small Presidio Bowl in San Francisco. People living up north have better prospects since somehow Sonoma County bowling has hung on longer. Petaluma’s AMF Lanes or Rohnert Park’s Double Decker Lanes may not be too far to drive.

But the bowling options for Marin’s 250,000 residents keep disappearing. High operating costs for utilities, property taxes, and maintenance have been a deterrent. Typically occupying large tracts of real estate, alley owners find it more profitable to sell the land to developers for housing or retail spaces. The pandemic kept alleys closed for long stretches. And the younger generation might be less attracted to the commitment of teams and leagues, which help keep alleys in business. The new or surviving lanes tend to be expensive high-end boutique chains or alleys buried in a few high tech, multi-activity, family entertainment centers. Run by corporations or private equity firms, these are a far cry from the old, family run, neighborhood alleys.

eared we were losing. In 2000, he predicted the revival of civic organizations and the “social capital” needed for a democracy. But it never happened. Instead, the country has experienced a decline in civility and the disappearance of community and national bonds. Of course, it goes beyond the loss of communal bowling and extends to most American institutions. A profound sense of political alienation has gripped the nation. In the 2017 book, One Nation After Trump, the authors showed that the decline of the civic and social groups (that Putnam championed) had helped elect Donald Trump as “many rallied to him out of a yearning for forms of community and solidarity that they sense have been lost.”

If recent Facebook and Reddit posts are any indication, Americans—including Marin residents--sorely miss the lost community of bowling and wish alleys would make a comeback. Maybe their revival wouldn’t hurt the country, either.

Robert Elias is emeritus professor of Politics at the University of San Francisco, a Marin History Museum volunteer, and editor of the Mill Valley Historical Society Review.